An effective operating planning process sets granular output and input metrics goals, prioritizes initiatives to achieve those goals, and makes corresponding resource (money, people) allocation decisions. A well-run process includes clear direction from the CEO, autonomy for each team to develop and propose detailed plans, a rigorous review process, and transparent decisions at the C-Level regarding which initiatives are approved and denied, resulting in alignment at all organizational levels. Progress versus goals for metrics and initiatives are reviewed weekly, monthly, and quarterly during the operating year.

In a world where your plan anticipates every possible outcome, you only need an inspection and auditing process to ensure the plan is followed. In practice, that never happens. Over the planning time horizon, new information about customer behavior, market conditions, competitor actions, and internal data may necessitate a plan change. So you not only need to measure quantitatively, “Are we proceeding according to the plan?” but also need processes to detect and react to signals that necessitate a change to the plan.

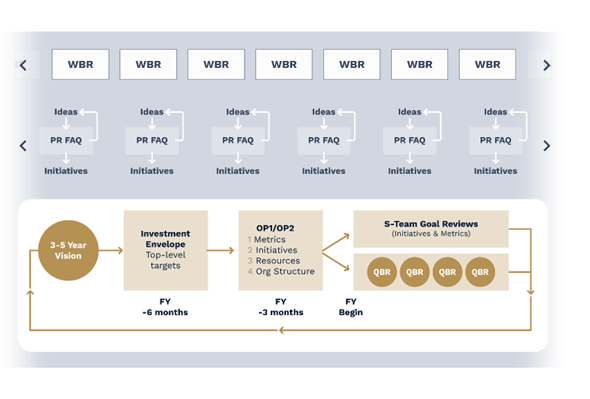

The process of planning, reviewing, and adjusting comprises the operating cadence.

The diagram above illustrates the operating cadence: the Weekly Business Review (WBR), Quarter or Monthy Business Review (QBR/MBR), the Working Backwards PR/FAQ process, and the annual planning process. This diagram does not include processes such as Agile product development, hiring, employee development, and organizational leadership reviews.

The Weekly Business Review (WBR) is at the top of the diagram. This process occurs every week, year-round. It is a comprehensive, data-driven exercise to answer three questions:

1. What did our customers experience last week?

2. How did the business perform last week?

3. Are we on track to hit our goals

Done right, it delivers unfiltered facts to tell you what has happened and where you are heading, regardless of where you want to be. How is the WBR related to planning, then? WBRs are a great source of insights about new actions you need to take, either to double down on what’s working well or to address a negative trend or problem that needs solving. This “swimming in the data” gives you a richer understanding of the business, operations, and customer experience, which in turn helps continually generate ideas to improve that customer experience. A simple example is looking at the top customer complaints in the WBR, which highlight areas where customers are having trouble or the company is not meeting their SLAs. Regardless of whether it is in the plan, the process identifies problems and opportunities requiring initiatives to fix defects, automate a process, or otherwise improve the customer experience.

The secret to Amazon’s prolific innovation isn’t a magic formula but rather a systematic process. The Weekly Business Review (WBR) and similar data-driven reviews are crucial. They embody the Amazon Leadership Principles of Customer Obsession and Dive Deep. They allow leaders to gain a deep understanding of current customer challenges and unmet needs—the core problems that require innovative solutions. This “swimming in the data” directly informs the Working Backwards PR/FAQ process, transforming identified problems into actionable initiatives to improve the customer experience.

The middle third of the diagram is also a continuous process throughout the year: the Working Backwards PR/FAQ process, which enables the ideation of product solutions to problems. It starts with an idea, refines it, and shapes it in a customer-obsessed manner into an actionable potential initiative. It is a lightweight tool for leaders to rapidly iterate and evaluate multiple new product ideas and select the one(s) with the most significant potential impact.

Innovation should happen year-round, not just in the planning phase. A common pitfall we have observed at companies is limiting the window of innovation to a few weeks per year during the annual planning process. This is a mistake for several reasons.

First, you can’t control when great ideas surface. You may be too late if you have to wait until the next planning cycle to vet the idea. Second, ideas and initiatives are not the same things. It takes several iterations through the PR/FAQ process to turn an idea into an actionable initiative. The annual planning process is brief and busy; four to eight weeks is not enough time for leaders at all levels to review the various iterations of PR/FAQ documents to determine the initiatives that will go into the plan. Finally, for any complex problem or challenging goal, you want to evaluate many ideas and choose among the best ones. Senior leaders at Amazon typically read and comment on several PR/FAQ documents per day, year-round.

The Working Backwards PR/FAQ process has allowed Amazon to run more experiments per unit of time versus other traditional product discovery methods, which has enabled it to evaluate a larger funnel of ideas in parallel. Constantly evaluating and refining a broad range of innovative ideas year-round not only increases your chances of hitting your goals (as well as making any adjustments to the plan promptly), but it also helps create higher-quality Annual Operating Plans.

The bottom third of the diagram is the annual planning process. The two main stages are:

Strategy –writing, reviewing, and approving of long-term strategy, investment envelope, and operating plans

Execution – auditing and control processes that happen throughout the year to ensure successful implementation of the plan and make any necessary changes to the plan

A detailed calendar of steps and deadlines should be established at the outset of the OP planning process. We recommend starting with the end of the process and working backward from there. Typically, the final step of the process is a presentation of the plan in November or December to the Board of Directors. The milestones preceding this, in reverse chronological order, include:

Assuming the fiscal and calendar year are the same, annual planning typically starts in June of the current year and ends in January of the following year.

| Process Step | Who | When/Duration |

| Develop & Deliver top-down guidance for Metrics, Initiatives, and Resources (Investment Envelope) | CEO & CFO | June (2 weeks) |

| Executive team offsite – vision document(s) | CEO & Exec Team | July (2-3 days) Optional |

| Function and Business Unit (BU) offsite meetings- vision document(s) | BU/Function leaders & team members | Aug (2-3 days) Optional |

| BU and Functions write OP1 plans, including Metrics, Initiatives, Resources, Org Structure, and P&L | BU/Function leaders & team members | Sept/Oct (4 weeks) |

| Financial plans for Function and BU loaded to Finance ERP system | Finance (FP&A) leaders | ?? (1 week) |

| BU & Function OP1 reviews with Division Exec | BU/Function leaders, Division Exec | Oct/Nov (2 weeks) |

| Business Unit (BU) & Function OP1 reviews with CEO & Exec Team | BU/Function leaders, CEO, Exec Team | Nov/Dec (1-4 weeks) |

| Finalize OP1 P&L, decisions, and goals for metrics initiatives & resources | CEO (Exec Team can assist) | Nov (1 day) |

| OP1 Review with the Board of Directors | CEO, CFO & BOD | Dec/Nov (1 day) |

| Determine Operating Plan 2 (OP2) plan based on Q4 actuals | CEO, Exec Team | Jan (1-2 weeks) |

A first step in annual planning is to write (or review if it already exists) a three- to five-year vision document. The vision document allows you to introduce and investigate trends, goals, or initiatives that span multiple years and eventually understand if and how your new annual plan will get you closer to realizing your long-term vision.

If the long-term vision is already established, another method is to start the planning cycle by writing short documents about important themes or trends to which the company should pay attention. Some themes can be externally focused, such as – “How do we live in a world where the customer has perfect information?” or “Is this web service thing for real, and if so, what can we do about it?” Some themes can be internally focused, such as “How to create a single store where Amazon is just another seller on the platform” and “How to increase software development speed.” Teams include lessons from the vision documents in their Operating Plans.

This step is optional. Not every team wrote a vision statement each year.

An effective operating planning process combines top-down direction with detailed, bottom-up plans from each business unit and function. They meet in the middle when GMs and functional leaders present their plan to the CEO and the executive team (known as the S Team at Amazon) for an in-depth OP1 (operating plan 1) review, during which they engage in debate and discussion to achieve alignment on the plan’s details. After the CEO and executive team have reviewed all plans, they decide which initiatives to fund and include in the company OP1 plan, which to cut, and make the corresponding resource allocation decisions.

The CEO and CFO use the outcomes of the offsite and vision document process and high-level P&L objectives to assign targets/goals for each business unit and function leader (referred to as the “Target” in this document). The Target goals are the output goals (and, in some cases, input goals) that act as a starting point for the plan. These may include targets for revenue, headcount, costs, and initiatives. Some companies refer to this as the Investment Envelope.

We have found that setting high-level targets saves time in the planning process and avoids unnecessary rework. Skipping the guidance step is likely to produce confusion at the team level. Without guidance, some leaders will build plans that are too aggressive in resource asks that the company is not prepared to fund, or their growth projections will be too far off from what the company needs. This can waste weeks of hard work, crush morale, and reduce confidence in the leadership team. Effective executives set clear direction and expectations before and during the planning process.

Determining the list of plans to be presented and the owner for each is a necessary input to establish the OP1 planning calendar. When the organization is small, coming up with this list is easy. As the organization grows, this becomes more complicated. To do this, determine how many days will be set aside for the executive team to review the OP1 plans and the time in hours to review each plan. By 2010, Jeff Bezos and the S-Team set aside more than two weeks for OP1 reviews and spent 2 to 4 hours reading and discussing each plan. How many plans need to be developed (and which plans need to be reviewed by the CEO and Exec team) varies from company to company based on several factors related to scale and complexity. With input from the executive team, the CEO and CFO should establish this list, add each to the “BU & Function OP1 reviews with CEO & Exec Team” calendar, and work backward from there. In our experience, establishing this list and schedule at the start of the process prevents thrash and frustration for middle managers.

For larger companies, many teams will have plans that don’t make the executive team review list. Each senior vice president or CXO must review such plans themselves and roll up the information into a plan that is being reviewed at the executive team level. Each executive team member must establish a calendar for reviewing the OP1 plans for their department, which precedes final reviews at the executive team.

Each business unit and function leader takes top-down guidance and develops a detailed plan with their reports, plus finance and Human Resources (HR) counterparts. The team must create a Target or Baseline plan corresponding to their assigned top-down revenue and cost/resource targets. Their plan includes SMART goals for metrics, initiatives, and resources to achieve the top-down targets.

In addition, each team is responsible for proposing incremental initiatives they would add to the plan if granted the corresponding incremental resources required. Each initiative should be backed up by a well-written and thought-out PR/FAQ document and should have at least T-shirt size estimates for revenue, cost, and headcount. The list of initiatives should be in priority order.

When you boil it down, there are just four parts to an Operating Plan.:

This includes the financial plan, other output metrics (e.g., Monthly Active Users, churn %), and the input metrics for the business or function. Clear goals are stated for each of the metrics at an annual level as well as quarterly, monthly, and possibly weekly levels (granularity drives precision and achievability). The process for identifying the right input metrics is not in the scope of this document—see Chapter 6 of Working Backwards.

Initiatives define the organization’s work to meet the metric goals in the coming year. Initiatives can include new business, product or feature launches, projects to drive out cost or gain speed, plans to implement a new process, and more. Ideally, each initiative is described in detail in a separate document, preferably a PR/FAQ or a written narrative. Conceiving, iterating, and refining initiatives should not be a once-a-year process timed to coincide with OP1. The process should be continuous. Each team should develop a backlog of projects/initiatives to be executed in the future. In a well-conceived OP1, the list of initiatives described is comprehensive, capturing (nearly) all work the team will undertake in the year ahead.

Resources are the tools that the business unit requires to fund their proposed initiatives (which will, in turn, enable them to achieve their stated metrics goals). Resources include OPEX (e.g., headcount/people costs, marketing $s, SAAS provider fees) and CAPEX (e.g., property, plant, and equipment). Resource requirements should be defined at the annual, quarterly, monthly, and, in some cases, weekly levels as precision drives achievement.

Having the right leaders and the right organizational structure is vital to the successful execution of proposed initiatives (and, therefore, meeting input and output metrics goals). You can’t achieve your initiatives if you don’t have the right people organized the right way. This does not mean that drafting an OP plan requires you to perform a reorganization. If the plan calls for minimal or no headcount growth, and the proposed initiatives are expected to be achieved by the current team and org, then no changes are needed. For ambitious plans with many new initiatives, new skills, and rapid expansion of the organization, it is incumbent on the Business Unit or Function Leader to propose the appropriate leadership team and organizational structure to meet the goals.

Once each team has completed the OP1 document, the executive leadership team sets aside several days (or weeks, depending on org size) to review every OP1 plan document, allowing ample time for healthy debate and discussion of the proposed initiatives and financials.

The CEO and executive team conduct rigorous testing to establish conviction that the identified initiatives, input metrics, and allocated resources are the correct drivers that will achieve the desired results; only then is their decision-making complete.

Here are some examples of the kinds of questions each Exec should ask as they read through each OP Plan:

At Amazon, each team would ask for more resources (headcount and money) than the prior year. This meant that there was healthy competition for the available pool of resources.

At the end of the process, the CEO (informed by the executive team) decides which initiatives are approved and which are not. This information is used to roll into an OP1 (Operating Plan 1) to be presented to the board of directors for approval.

Because OP1 plans are written in August and September and reviewed in October, each plan includes estimates for output and input metrics for the fiscal year’s last three to five months. Once the fiscal year ends, these forecasts are converted to actual results. Adjustments are necessary when there are significant variances between estimates and actual results. When the company exceeds or falls short of forecasted revenue or operating expenses, it adjusts the plan by reducing or increasing the number of approved initiatives, resources, and metrics goals. The executive team meets in early January to review the variances and decide on revised metrics, initiatives, resource allocation, and goals. These are subsequently communicated to each BU and Function leader. They, in turn, work with their teams to revise each OP1 plan based on actual results and revised top-down goals. By the end of January, these modifications resulted in the OP2 plan, which became the record plan.

At Amazon, during the OP1 reviews with Jeff Bezos and the S-Team, they would devote some of the discussion to selecting or assigning what they considered to be the most important goals for each team and the company.

For example, one business unit’s plan might include goals for 20 metrics and 20 new initiatives. During the OP1 review, in addition to suggesting modifications to the goals, Jeff or another S-Team member might designate some of these metrics or initiatives as S-Team goals. This occurred in each review. Roughly 15% of the initiatives and metrics reviewed also became S-Team goals.

Jeff Bezos describes this part of the planning process in his 2009 Letter to Shareholders:.

Our goal setting sessions are lengthy, spirited, and detail-oriented. We have a high bar for the experience our customers deserve and a sense of urgency to improve that experience.

We’ve been using this same annual process for many years. For 2010, we have 452 detailed goals with owners, deliverables, and targeted completion dates. These are not the only goals our teams set for themselves, but they are the ones we feel are most important to monitor. None of these goals are easy and many will not be achieved without invention. We review the status of each of these goals several times per year among our senior leadership team and add, remove, and modify goals as we proceed.

The S-Team spent roughly 75% of their meeting time reviewing S-Team goals and trying to remove any roadblocks blocking a goal. The progress for S-Team goals was carefully monitored. Each leader was required to report their progress against each goal and meet with the S-Team quarterly to provide detailed descriptions of their solutions to get yellow and red projects back to green. This part of the process drove accountability and focused executive attention to the most critical items.

S-Team goals are very Amazonian. However, other tools and processes, such as OKRs, can accomplish the same objective.

Good auditing and control processes ensure appropriate progress is made versus the plan and provide forums and timing to adjust the plan as new information arrives.

In addition to the S-Team goal process, leaders are held accountable for results in weekly business reviews (WBR) and monthly or quarterly business reviews (MBR/QBR). Every business unit conducts a quarterly or monthly business review (MBR) with the appropriate senior leadership members (VP, SVP, or CXO, depending on the team) in attendance. The written review covers progress against the team’s OP plan goals for metrics and initiatives and discusses any proposed changes to the plan.

During the operating year, Amazon, BU, and Function leaders needed S-Team or CEO approval to change their OP plan goals for metrics and initiatives or to add more resources than what was approved in their Operating Plan. Most changes required S-Team and CEO visibility and approval. This high level of friction was intentional. With friction, the goals and resource allocation decisions made during the OP planning process remain meaningful. Alternatively, the organization’s time and effort were wasted on a meaningless bureaucratic exercise.

However, the process must be flexible so teams can remain agile and respond appropriately as new information arrives from customers, the market, and competitors. It was common for teams to update and modify their initiative roadmap throughout the year, with the proper signoff from a VP, SVP, or CXO as appropriate. Sometimes, a new initiative can be identified using the Working Backwards PR/FAQ process during the plan year, and it can be added to the roadmap with existing resources without jeopardizing S-Team goals. Teams could be agile while achieving company goals and managing costs. We found this tension provided the best balance between maintaining alignment and giving leaders the freedom and autonomy to experiment while ensuring company goals were met.

Metrics first.

The most common defect of an OP plan is the need for a comprehensive set of metrics (outputs and controllable inputs) with results from the prior year, the current year, and the target/goal numbers for the following year. There are many things that a leader can and should delegate. Selecting the right metrics to guide the organization’s work is not one of them. Without the right metrics, a team and company will veer off the path in ways that prevent the organization from achieving the right results (see our example regarding the ‘selection’ metric in chapter 6, page 126).

Define the problems and opportunities.

When describing the current state of the business/function (section 3), describe the current problems and opportunities for improvement using data. Without a cogent analysis of the current state of your business (problems and opportunities), you can’t identify the right initiatives. For example, compare these descriptions of a product problem;

a) Prime Video click-to-play time (CTP) increased from 320 ms to 467 ms in Q3/22.

b) Prime Video click-to-play time (CTP) increased from 320 ms to 467 ms in Q3/22 (+212 ms vs. goal of 252 ms), driven by iOS CTP increasing from 259 ms to 715 ms (iOS is 32.2% of WW video playback) as a result of a bug in version 6.7 of our iOs app released on 8/22/22.

The possible initiatives to resolve problem ‘a’ are guesses relative to the precise remedies for problem ‘b.’

Define Initiatives in detail.

Initiatives are the solutions to problems and opportunities. Describe what you plan to build before you build it. Each initiative must include details demonstrating a clear understanding of the required scope, time, and resources. Defining work enables teams to achieve autonomy, trust, and alignment with the CEO and leadership team. Compare these two different descriptions of the same initiative:

a) Launch Amazon Prime Video in South Korea in 2023

b) Launch Amazon Prime Video in South Korea on 9/15/23 with Korean language translation, a team of 4 content managers, 10 CS reps (located in Seoul), 2,400 movies, 3,600 series, and native apps for Fire TV, Roku, Sony, LG, iOs and Android, with a tp90 CTP of 300ms, resulting in 875k new Prime members in Q4/23.

The detail and precision of option ’b’ put a clear stake in the ground, which the CEO and leadership team can debate, discuss and ultimately gain alignment on the details in the OP review.

Separate one-way door from two-way door decisions.

Fixed cost decisions are long-term, one-way door decisions. Variable cost decisions are two-way doors (e.g. marketing spend, temp labor, training budget). You can adjust two-way door decisions throughout the year. Devote the majority of time and discussion to one-way decisions.

You can control costs and initiatives.

If you set a goal not to exceed x$ in fixed and variable costs, or launch a new product by a specific date, with the right plan, leaders, and processes, you can achieve your goals. Devote the majority of time and discussion to these controllable activities.

You can forecast revenue, but you can’t control it.

Forecasting revenue is an important step in OP planning. But, it is important to acknowledge that you cannot control the results because many variables are out of your control. Even a well-constructed plan with the right initiatives does not ensure success because you don’t know which initiatives will succeed or fail. External forces (economy, pandemic, supply chain constraints, etc.) often influence your revenue more than your initiatives. This is why the work and discussion should be centered on the things that you control; input metrics and initiatives.

Revenue forecasts should be based on the current realities and trends of your business. Refrain from basing forecasts on rosy expectations for new initiatives or through “pushing the team” to hit aggressive revenue targets (good intentions don’t work). Detailed plans executed by effective managers and single-threaded teams were (much) more effective management methods.

At Amazon, we learned to exclude or hedge projected revenue for new initiatives in our financial plan because our projections were usually (very) wrong. Many new initiatives failed to produce any incremental revenue, or it took months or years for the new business to deliver positive results. Others had surprisingly positive results (Echo/Alexa) that exceeded our expectations. We managed these in the risks and opportunities (R&O) bucket.

Identify dependencies.

Manage dependencies by including them in the plan to avoid mid-year surprises. A common mistake is for teams to put a new initiative in their plan, which requires support from one or more teams outside of their scope of control without identifying the specific resources and gaining alignment/commitment from the leaders managing those dependencies. Preview the plan in draft form with appropriate cross-functional (tech, legal, marketing, PR, finance, HR, etc.) leads before presenting the plan. Call out cases where dependent teams have not committed resources. The cost to resolve a dependency only increases over time. Therefore, your planning process is the best time to discover and resolve dependencies.

Think Big.

To achieve big, step-wise improvements to your business, you have to think big. Small thinking manifests itself in laundry lists of initiatives that require little time and few resources, are low in risk, and seek incremental gains measured in six or seven figures. For sure, a good plan includes some initiatives that have these qualities. Balance these by allocating the appropriate portion of your resources to big, risky (but well-thought-out) initiatives that have the potential to deliver big results.

Decide what not to do.

If an OP plan lists 20 initiatives, but the team only has the resources to complete 10, the right approach is to debate and decide which 10 to prioritize and build and which 10 they should cut. Ruthless prioritization will improve your company’s ability to deliver the right results by focusing resources on the initiatives with the greatest potential return.

Create customer value.

When evaluating the initiatives in an OP plan, consider whether each initiative will improve the customer experience or not. Initiatives like optimizing funnel conversion, increasing brand awareness, and reducing CAC, produce more revenue but don’t necessarily create value for customers. Be sure that a meaningful portion of resources are devoted to new products, features, and services that solve customer problems or address unmet needs.

Section 1 – Introduction

1/4 page). Briefly describe the business or function, the team, responsibilities and scope. If the team has established or wishes to propose any tenets, include them here.

Example: “This is the 2023 annual operating plan for the Trust & Safety (T&S) team. The team is led by [name and title here], and is comprised of two sub-teams; (1) Trust led by [name] is an engineering team of 15 (1 Director, 10 SDEs, 2 PMs, 2 SDET) and (2) Safety lead by [name] is an engineering and operations team of 25 (1 Sr Mgr, 18 SDEs, 6 PMs). The scope of our team’s responsibilities includes…

Section 2- Metrics

(1 page or less). This is a table of the most important metrics (more than 5, less than 20) for measuring and understanding the business (or function). This table should use a combination of input metrics (input metrics are controllable, mostly customer-facing, and part of your growth flywheel), and output metrics (financial and other commercial metrics). The table should show values for the prior year, the current year-to-date, the current year projection, and the goal for the next year. Include the year-over-year percentage change for each. Other or more detailed tables of metrics (e.g. P&L) should be included in the appendix. Invest the time to propose a robust list (~8 to 15) of metrics. Your proposed metrics goals should define a successful year for your team. More detailed tables of metrics (e.g. P&L) should be included in the appendix.

Key Metrics (Inputs & Outputs)

Summary Of Key Metrics (Outputs and Inputs)

| 2021 | 2022 (YTD) | YTD YOY % | 2022 Plan/F’cast | 2022 Plan/F’cast YOY% | 2023 Plan/F’Cast | 2023 Plan/F’cast YOY% | |

| Net Revenue | |||||||

| Product Line A | |||||||

| Product Line B | |||||||

| Product Line C | |||||||

| New Customers | |||||||

| Active Customers | |||||||

| Total Marketing ($) | |||||||

| Online Marketing ($) | |||||||

| Customer Acquisition Cost ($) | |||||||

| LTV/CAC | |||||||

| CS Contacts Order | |||||||

| TP 90 App load time (ms) | |||||||

| TP90 Click to Deliver Time | |||||||

| TP90 Detail Page Load Time (ms) |

Section 3 – Review of the Prior Year & Changes in Consumer or Industry Trends

1-2 pages. This section is designed to recap the prior year. There are four parts to this section:

a) Commentary on the key metrics table. Explain and describe the key variances reflected in the table of metrics.

b) Description of the key outcomes and initiatives completed in the prior year. It is important to capture what you said you would deliver in the plan for the previous year and where you did and did not deliver versus the plan. What was the blocker for things that you did not deliver?

c) Wins, mistakes, misses, and key learnings from the prior year. What worked, what didn’t work, what mistakes did your team make, and what learnings are you capturing and incorporating in the go-forward plan.

d) New trends or changes that are relevant from a customer, competitor, economic, or industry perspective.

Section 4 – Key Initiatives

2-3 pages. The Key Initiatives section defines the work the organization will undertake in the coming year to meet the metric goals articulated in section 2. In a well-conceived OP, the list of initiatives described is comprehensive, capturing (nearly) all work that the team will undertake in the year ahead. Initiatives can include new business, product, or feature launches, projects to drive out cost or gain speed, plans to implement a new process, and more. In some cases, it is also important to describe one or more core operations in your function or business, how many of your resources will be allocated to the operation, and any goals (tied to metrics) for process improvement in the coming year.

S.M.A.R.T. Each initiative is described using one or two paragraphs. Each initiative must be S.M.A.R.T. (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Timely), so make sure to include the following elements in the description: a specific (but concise) description of the initiative, the leader(s), the start and end dates, the projected impact on key metrics, the resources that will be allocated to the initiative (e.g. 5 SDEs, 1 PM, 1 Design…), and any fixed or variable non-headcount costs (e.g. $12m marketing budget, or a $200m new fulfillment center.) A corresponding table of the key initiatives should appear in Appendix 2.

Baseline vs. Incremental. Be sure to list all of the initiatives in priority order and indicate which initiatives are in your baseline plan (which can be accomplished with your current resource allocation), and which would require the approval of incremental resources.

Dependencies. Identify any dependencies (technical, people, budget $s) on other teams required for each of your initiatives. Ideally, before finalizing your OP document, you can have a conversation with each team that represents a dependency to verify whether or not they plan to support and resource your initiative(s) or not. That is, you want to determine whether your initiative(s) will also appear in the dependent team’s OP plan or not (and note this in your plan).

PR/FAQ. Ideally, each initiative is described in more detail in a separate document: a PR/FAQ or a written narrative. These should not be read/reviewed as part of the OP planning process (insufficient time). Instead, conceiving, iterating, and refining initiatives via PR/FAQ should occur continuously so that each team can develop a prioritized backlog of initiatives to be executed in the future.

Section 5 – Resources

One page or less. This table summarizes the team’s composition today and the planned composition for the next year. This table is most relevant in cases where the plan requires changes (upwards or downwards) in resources (otherwise, it simply captures the current org). Break down the team by role/level and capture how many HC for each/ today and plan to have next year. The allocation of these resources should be described in the prior section initiatives but can also be articulated here based on the current or proposed structure of the team (e.g. how your org is subdivided into various single-threaded teams). Be sure to list all of the initiatives in priority order and indicate which initiatives are in your baseline plan, and which would require the approval of incremental resources.

Non-Headcount Fixed and Variable Costs. Also include a table of any other variable costs within your current and proposed budget (e.g. marketing spend, temp/agency fees, cost of SAAS products, etc).

Appendix 1 – P&L (or more detailed metrics tables)

Summary of the prior year and current year financial results along with the financial plan for next year.

Appendix 2 – Table of Key Initiatives

# | Name | Short Description | Owner | Start | End | Key Metric(s) goals | Project Resources | Permanent Resources | Dependencies |

Baseline Initiatives | |||||||||

1 | Project Rhine | Launch Germany where localized means a) all text translated to German, b) CS support in German, c) adding new payment types, c) meeting regulatory requirements x, y, and z. [Insert link to PR FAQ Doc] | Tom H | 10/1/22 | 5/15/23 | DE 1st contract starts; 1.6 MM (+430% YoY) , DE Enterprise Rev $55 (+359% YoY) | 10 SDEs, 4 Design, 2 PMs… | CS Manager, 10 CS, Country Manager, 1 legal, 1 finance, 1 HR… | 10 CS, 1 Legal |

2 | Project Refactor | Project Refactor is the first phase in our transition from a monolithic codebase to a service-based architecture. Four teams/services (payments, identity, search, and browse pages) are in scope for this phase. Each team will develop a plan to establish, build and deploy a new service (and a set of internal facing APIs) to replace the current functionality within the monolith. [Insert link to PR FAQ Doc] | Jen R | 9/1/22 | 11/15/23 | Reduce Sev1 tickets from 12/month to 2/month (-83%), reduce Sev-2 tickets from 37/month to 6/month (-78%), reduce deployment time from… | 67 SDEs, 10 SDET, 3 Design, 10 PM, 5 TPM | ||

3 | Project Retro | Launch Free shipping service for purchases of $25 or more [PR/FAQ link] | Sue F | 11/20/22 | 1/28/23 | Grow avg transaction size from $18 to $26 (+44%) | 3 SDEs, 1 Design, 2 PMs… | 1 Legal, 1 FP&A | |

4 | Project Green | Launch solar drone delivery | Lyn R | 1/12 | 8/15/23 | Reduce carbon emissions per shipment from 12 ppm to 5 ppm | 4 Hardware Eng, 5 SDET, 6 SDEs, 1 Design, 2 PMs… | ||

Incremental Initiatives | |||||||||

6 | Project Yellow | Enable Google Pay and Apple Pay at Checkout | Don R | Increase cart to ship conversion rate by 320 Bps | 9 SDEs, 2 Design, 2 PMs… | ||||

7 | Project Stingray | Redesign order pipeline to reduce customer actions steps from 6 to 4 | Jon L | Increase cart to ship conversion rate by 450 Bps | 5 SDEs, 3 Design, 2 PMs… | ||||

Appendix 3 – Table of Resources/Headcount

List of detailed headcount plans.

Appendix 4 – Product Roadmap and Headcount Allocation

List the allocation of resources for your product roadmap by month. Create a baseline allocation for each initiative. In a separate chart, create a table with your incremental ask of resources. Sum the resources at the end.

Your goal here is to clarify what you will deliver with no additional resources, with your additional ask. This section is also helpful so the management team can look at what happens if you get a partial allocation of the resources you request.

Appendix 5 – FAQs (optional)

Q: What are the most important decisions that we need in this meeting?

A:

Q: What is the single biggest thing we can do to move the need in this business and how will we organize to do just that

A:

Q: What are your disruptive ideas? [new/bold/risky product ideas or initiatives that are likely to fail but if they were to succeed, would result in a step-change in revenue/customer growth, cost reduction, or enable you to build a moat/relative advantage vs your competitors.]

A:

Q: What new initiatives and/or product ideas did you investigate that you chose not to include in the plan, and why didn’t they make the cut?

A:

Q: What were the positive and negative surprises in 2022? What are the specific measures you put in place (initiatives, processes, or structural changes) to address these surprises?

A:

Q: What are your top misses and learnings? What are you most disappointed about with your division/product/business in 2022?

A:

Q: Are there any programs or initiatives in your business that don’t have a single-threaded leader?

A:

Q: Do any customers, business partners, or suppliers represent greater than 20% of your business? If so, what are you doing to reduce your dependency on these partners

A:

Q: What dependencies do you have in your business today that you wish you controlled?

A:

Q: What “dogs not barking” do you worry about? [In other words, what are potential blind spots for you where you don’t have reliable data/information about your competitors/customers/the industry that could have a big impact on your business.]

A:

Your goal here is to clarify what you will deliver with no additional resources, with your additional ask. This section is also helpful so the management team can look at what happens if you get a partial allocation of the resources you request.