Input metrics are the drivers that, when managed well, can lead to the desired outputs: profitable growth in revenue and customers. The right choice of input metrics will deliver clear, actionable guidance. A poor choice will result in a statement of the obvious, a non-specific presentation of everything your company is doing. Donald Wheeler, in his book, Understanding Variation: The Key to Managing Chaos, explains:

“Before improving any system…you must understand how the inputs affect the system’s outputs. You must be able to change the inputs (and possibly the system) to achieve the desired results. This will require a sustained effort, constancy of purpose, and an environment where continual improvement is the operating philosophy.”

Controllable, customer-facing input metrics are just as the name describes:

a) Controllable– these are factors that your company can control through your team’s actions and initiatives. In the case of Amazon, these activities/initiatives include adding more items to Amazon’s store, reducing costs so prices can be lowered, or positioning inventory to facilitate faster delivery to customers. Output metrics like orders, revenue, and profit are essential but generally can’t be directly or sustainably manipulated over the long term.

b) Customer Facing- the inputs are the factors that positively improve the customer experience. Each sustained improvement in the customer experience creates long-term value for customers. Customers win when Amazon improves and adjusts its operations to reduce order-to-delivery time from 3 days to 1 day.

Some companies refer to these as leading indicators, but we prefer a more precise term: controllable input metrics. As a leader, you make deliberate decisions about allocating resources—such as people, equipment, software, marketing budgets, or geographic expansion—to drive those input metrics in the desired direction.

Thus, input metrics are things that, when done right, improve the customer experience, create value, and bring about the desired results in your output metrics, like sales, profit, and share price.

Output metrics are lagging indicators—they measure the results of the inputs. Output metrics include financial metrics like revenue, gross profit, free cash flow, and other metrics like active customers, new subscribers, churn rate, and customer satisfaction. They are important but generally can’t be directly manipulated sustainably over time.

So, how do you figure out the input metrics for your company? It sounds easy, but discovering (really uncovering) your input metrics is an iterative process that takes months and years. Here is how to get started.

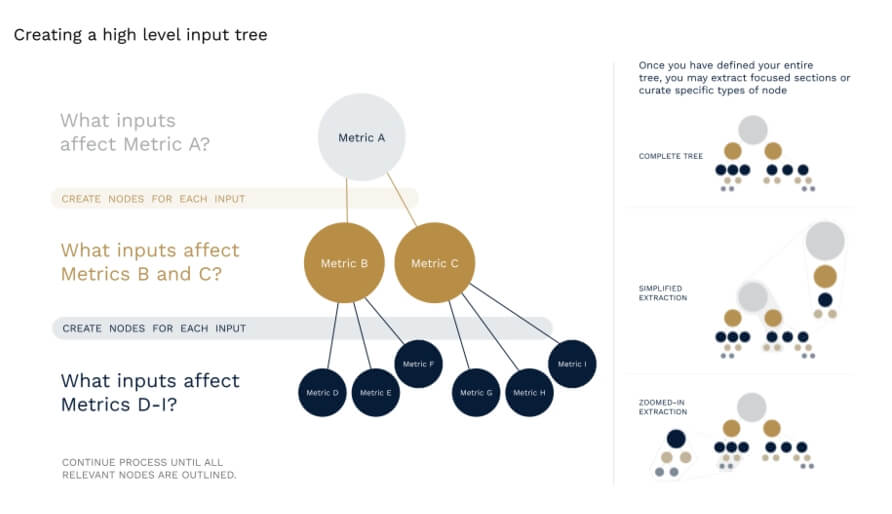

This method is a simple but very effective technique. To build a Metrics Map, start from one of the goals your team or company has been asked to achieve or any critical metric, whether it is output or an input, and ask yourself, “What factors drive this metric, and how can I measure them? “ Capture these and then repeat. Keep recursively drilling down each node until you can go no further. Then move on to your next important goal or metric that you are responsible for, and repeat the process, going downward and outward until you’ve hit the end of each branch or node, and you can’t go any further. Don’t worry if some metrics are repeated in the graphs. How many downward and outward levels will you need to go? There is no standard depth– it varies in each case.

Identifying the nodes that affect each input and developing the right metrics to measure each is a continuous and interactive process. This can and will result in a list of hundreds of metrics.

How do you know when to stop adding metrics? The answer is that you stop when the metric/activity cannot be meaningfully decomposed any further – e.g., “reduce search page latency.”

The easiest way to get started with Metrics Mapping is to begin with your output metrics as a top-level node and then drill down on each node.

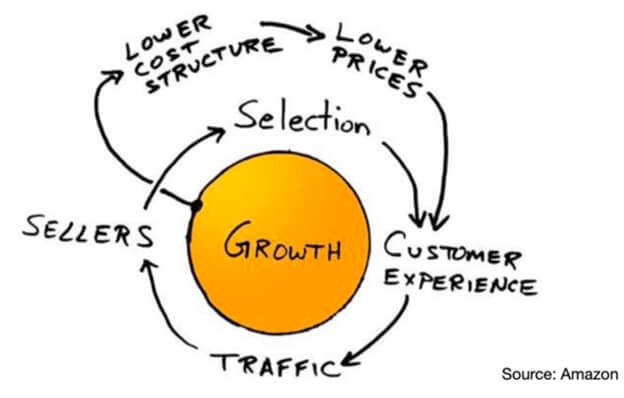

Jim Collins’ book, Good to Great, greatly influenced Amazon. If you haven’t read the book, we highly recommend it. Jim Collins introduces the concept of a growth flywheel. In short, the flywheel elements describe the activities of your business that form the intersection of a) your passion, b) where your company can be best in the world, and c) what drives your economic engine.

From the early days at Amazon, Jeff identified a vision of enabling customers to find, discover, and buy anything online. Later, using the flywheel analogy, he broke this down into discrete inputs: selection, low prices, and customer experience (e.g., find what you want and get it shipped to your home fast). Selection, price, and customer experience are the drivers of Amazon’s flywheel, and each happens to be a controllable, customer-facing input. Here is Amazon’s flywheel.

Once you have created your flywheel, you need to consider the factors that affect and drive each flywheel element.

Think of your metrics as an upside-down tree with branches or nodes spreading outwards and downwards from a starting point of one of your business’s flywheel elements. Each flywheel element is affected by other inputs, which are, in turn, affected by another layer of metrics, and so forth. Keep going until you bottom out.

One of the best ways to identify your inputs and their drivers is to map out the end-to-end customer experience for your product or service and then identify potential inputs and corresponding metrics. Simply break down the customer experience into steps, capture each step in a diagram or a spreadsheet, and then brainstorm potential inputs and metrics for each step. For each stage, ask what metrics measure its speed, quality, cost, and efficiency.

Mine your data from the Customer support organization to measure the volume of contacts related to each customer problem/issue and review this in the Weekly Business Review. This way, we always knew what problems our customers were encountering that week and were focused on how to reduce the frequency of each type of problem. Spend time with customer support representatives to learn about the problems they encounter most frequently for each product or service.

In the early years of Amazon, the management team of Amazon had to step away from their desk jobs during the holiday rush, answering customer service requests or working in the fulfillment centers to pick, pack, and ship customer orders so we could ensure a positive holiday experience for our customers.

If you are a B2B company, you should regularly sit in on sales calls and review Salesforce metrics to understand why deals close and why they don’t.

There is no substitute for firsthand encounters with customers and fulfilling their orders. Seeing, hearing, touching, and experiencing your operations is more memorable and emotional than reading about it in a report.

Everyone makes mistakes. We published a Root Cause Analysis (called a Correction of Errors internally at Amazon) for significant mistakes and made plenty of them at Amazon. We tried to talk openly and plainly about our mistakes so everyone could learn from them.

But did you know that mistakes and defects are excellent sources of input metrics you have yet to discover? When a defect occurred, we would ask this simple question: What metric or metrics should we have measured to predict or prevent this defect from occurring?

We often did not have the systems to measure the metrics that answered this question. So the following two questions would be:

“What do we need to build to measure this metric”?

And

“When will it be in our Weekly Business Review”?

These methods are not mutually exclusive. Use them in parallel. Also, it helps to perform this process as a team where you can brainstorm with each other. At this stage, it’s vital to identify what metrics you want to track rather than what metrics are available today. As you discover your input metrics, you likely will find systems or processes that do not record the data you need (we call this instrumentation). There may be some instrumentation work the engineering team needs to build to collect this data.

1. At the outset, try not to limit your thinking to what you can and cannot measure; just focus on the customer journey. Once you have filled out the spreadsheet, meet to review, debate, discuss the various metrics, modify the list, and (finally) assign each priority. This prioritization will drive the following work to gather the data and calculate and visualize each metric in a WBR report.

2. Avoid selecting and predicting which of the potential input metrics is the most important. This is largely unknowable at the start of the process. It is easier to predict the value of a metric once you establish a WBR using the 4-blocker visualization method and have observed changes in the metric over time and how those changes correspond with other metrics.

3. Make sure to include the output metrics. We started every WBR at Amazon by reviewing our progress against our financial plan for the quarter. Adding input metrics to your management dashboard doesn’t mean removing your outputs. It is imperative that you review them together to determine which inputs and corresponding metrics make an impact. If you move the right input metrics in the right direction, the result will be positive growth in one or more output metrics.

4. Err on the side of too many metrics rather than too few at the outset. You must throw spaghetti on the wall at this phase and then see what sticks. The list of metrics you review in your WBR is ever-changing — you are continuously subtracting, adding, and modifying the metrics. At the outset, use your best judgment to prioritize the list of metrics and the corresponding work your engineering and BI teams will need to do to

capture the appropriate data and calculate each metric.

5. Ensure you allocate sufficient resources from your BI or data analytics team to capture the correct data,

compute accurate metrics, and enable seamless and rapid reporting.

Before explaining how to start running the WBR meeting, let’s take a step back and discuss why this meeting was an essential mechanism of the operating cadence at Amazon.

Have you ever heard someone share the conventional wisdom that CEOs and Executive leaders should focus on a short list of the “most important metrics?”

Or how about the notion that once you become a senior leader, you should stay high, focus on strategy, and leave the business details to your subordinates?

This is the kind of conventional thinking that Jeff Bezos rejected. Jeff thought this was not an either-or proposition. It was an AND. Why is it written that you have to choose one or the other? Why isn’t it possible to manage strategy AND the business details, too? The rejection of this conventional wisdom was so important that it was codified as one of Amazon’s Leadership principles:

Dive Deep

Leaders operate at all levels, stay connected to the details, audit frequently, and are skeptical when metrics and anecdotes differ. No task is beneath them.

The weekly business review at Amazon is one of the mechanisms established to solve the problem of managing strategy and staying connected to the details. The Amazon WBR report covered more than 200 metrics, and the meeting was conducted in just one hour.

The leader and sometimes team members owned their metrics for each department, and it was their responsibility to explain the results. The metrics owners were not analysts, although every one of these owners had analysts to support them. They were the business or functional owners themselves, and it was their job to understand their metrics in-depth.

Each owner was prepared. They knew in advance which metrics to skip over (because there were no notable changes) and which metrics to focus on and explain in more detail. Typically, each department leader conducted a team or department-level WBR meeting before the all-company meeting to facilitate an in-depth understanding among the top leaders of each team in the company.

The goal of the meeting is to understand what is happening with the customer experience and your business. Create an environment that is conducive to the process of finding the brutal facts. Progress is made when you gain insights into what kinds of initiatives and events produce both positive and negative results to inputs and outputs, plus understanding how your metrics affect each other.

Most companies review metrics using some combination of many tables of metrics or charts with different visualization methodologies. Frequently, their reports use a variety of visual representations of data. While I’m sure there are cases where metrics are better understood with different visualization methods, this creativity results in cognitive overload for the report’s audience in most cases. Each new table or chart requires time to orient and interpret the results.

Over time, we determined that the cognitive overload wasn’t worth the theoretical benefits of varied chart and table formats. Instead, we took the approach that the priority was to reduce cognitive load and increase the ability to gain information about each metric rapidly. We hypothesized that, with proper visualization formats, we could create a report that enabled the Executive team to scroll through hundreds of metrics in less than one hour while gaining valuable insights and clarity on what parts of the operation were on track and off track.

Jeff was focused on how we could all use the most powerful tool at our disposal to make sense and identify patterns in the Data – our brains. Here is a quote from Jeff on this topic.

“Humans are unbelievably data efficient. You don’t have to drive 1 million miles to drive a car, but the way we teach a self-driving car, you have to drive a million miles.”

The Weekly Business Review report format included a handful of tables for metrics like the P&L, but most notably, most metrics are all depicted using the same line-chart format. Because every metric is graphed similarly, there is zero cognitive load. Instead of spending brain cells orienteering on the chart or table format, the brain is focused on the information and gathering insights. The format makes it incredibly easy to spot trends and gain a nuanced understanding of hundreds of metrics.

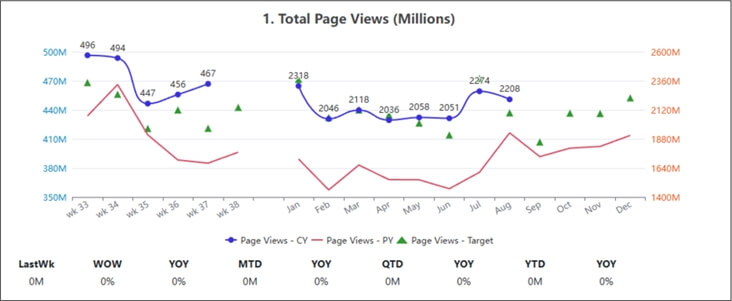

Let me show you an example of how this works. Let’s look at a metrics page using the Amazon weekly Business review report style in the 4-blocker or 6-12 report format.

Notice how easy it is to track and observe changes for each metric based on how the lines move. For each metric, the chart plots the six-week trend and the twelve-month trend side by side. On the left side of the chart, you see lines representing the prior six weeks; the second line beneath it is the same metric for last year for the same weeks the previous year.

On the right-hand side of the chart, we depict the results plotted for the last 12 months versus those from a year ago. In addition to plotting the year-over-year (YOY) results, you can also plot a goal or plan number. The net result is you can observe micro and macro trends, what’s been happening the last 6 weeks and the past 12 months too.

Finally, a row of metrics at the bottom of each chart provides the month, quarter, and year results compared to prior periods. This format delivers high information density for each metric within ¼ of a printed page.

Assigning a number to each metric in ascending order is a best practice. This makes it much easier for everyone to navigate the report.

Nearly every metric is visualized using this same graph format. Where appropriate, some metrics are presented in compact tables, like a P&L plan vs. an actual-to-date summary. With most metrics displayed using this same graphical format, it is easy to spot variances, changes in trends, and metrics that are above or below plan.

In our experience, the “One Metric That Matters” philosophy is fundamentally flawed. It assumes that your business is one-dimensional and thereby glosses over the multi-dimensional complexity inherent in every industry. A detailed understanding of how your business works is vital to effective decision-making.

We are frequently asked what research Amazon conducted to decide what products to build and actions to take. We answer that leaders at Amazon spent their time swimming in a sea of input metrics. By being in touch with every end-point and every aspect of the customer experience, we could see how the parts were interconnected and understand our customers and our processes to spot opportunities and defects at a level of depth that few companies achieve. This detailed understanding produced new ideas for what to invent on behalf of our customers and better decision-making at every level of the company.

As discussed earlier, this doesn’t mean all metrics are created equal. The management team’s work is to identify the most critical input metrics to drive and to understand the drivers of each. At the same time, tracking a constellation of input metrics is advised because if one of those metrics starts to shift out of an acceptable range, it can signal a customer-facing or process defect. You cannot anticipate the cascading effects of every action, and swimming in the data is a way to manage this challenge.

For more on the topic of One Metric That Matters (and input metrics), we recommend reading this article on the topic from Reforge: https://www.reforge.com/blog/north-star-metric-growth

New and active customers drive sales and revenue outputs. Reviewing marketing spending by channel and customer acquisition cost is essential to a WBR. How much, how, and where you invest your marketing dollars and measure the return (LTV/CAC and $ spend/incremental revenue) are all crucial decisions requiring continuous monitoring and adjustment

A metric can be an input metric that drives another metric. It can also have a set of input metrics that drive it. So, the answer to the first question is “Yes.” Don’t get too hung up on whether a metric is an input, output, or both in this brainstorming and discovery process. But you should avoid cases where you have identified an important metric, one you cannot directly control (i.e., an output metric), and you have not identified any input metrics that drive it.

No, but most of them probably will be. However, some critical controllable input metrics are not customer-facing but significantly impact your output metrics. One example is inventory record accuracy. If you don’t know exactly where each item is stored across your fulfillment network, ensuring that you keep your delivery promises to customers will be challenging. A second example is Days Payable. If you strive to be a low-cost provider where every penny counts, then measuring, analyzing, and controlling your company’s Days Payable portfolio frees up precious capital that can be deployed elsewhere.

1 Donald J. Wheeler, Understanding Variation: The Key to Managing Chaos (Knoxville, TN: SPC Press, 2000), 13.